|

v1.1.0

|

Details on the Sifteo graphical architecture

Sifteo cubes have a fairly unique graphics architecture. This section introduces the main differences you'll notice between Sifteo cubes and other systems you may be familiar with. We assume at least some basic familiarity with computer architecture and computer graphics.

The display on each Sifteo Cube is the star of the show. It's what sets Sifteo Cubes apart from dominos, Mahjongg tiles, and most other tiny objects people love to pick up and touch and play with.

Our displays are 128x128 pixels, with a color depth of 16 bits per pixel. This format is often called RGB565, since it uses 5 bits of information each to store the Red and Blue channels of each pixel, and 6 bits for Green. (The human eye is most sensitive to green, so we can certainly use an extra bit there!)

This RGB565 color representation is used pervasively throughout the Sifteo SDK and Asset Preparation toolchain. To get the best quality results, we always recommend that you start with lossless true-color images. The asset tools will automatically perform various kinds of lossless and optionally lossy compression on these images, and any existing lossy compression will simply hinder these compression passes. Your images won't be looking their best, and they will take up more space! Yuck!

In particular, here are some tips for preparing graphics to use with the Sifteo SDK:

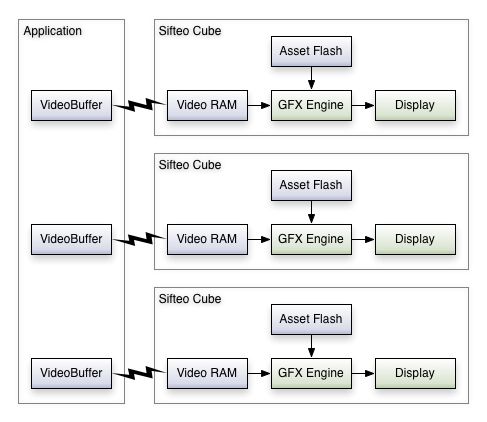

Unlike most game systems, the display is not directly attached to the hardware your application runs on. For this reason, Sifteo cubes use a distributed rendering architecture:

Each cube has its own graphics engine hardware, display hardware, and storage. Cubes have two types of local memory:

This distributed architecture implies that many rendering operations are inherently asynchronous. The system synchronizes Video RAM with your Sifteo::VideoBuffer, the cube's graphics engine draws to the display, and the display refreshes its pixels. All of these processes run concurrently, and "in the background" with respect to the game code you write.

The system can automatically optimize performance by overlapping many common operations. Typically, the cube's graphics engine runs concurrently with a game's code, and when you're drawing to multiple cubes, those cubes can all update their displays concurrently.

In the SDK, this concurrency is managed at a very high level with the Sifteo::System::paint() and Sifteo::System::finish() API calls. In short, paint asks for some rendering to begin, and finish waits for it to complete. Unless your application has a specific reason to wait for the rendering to complete, however, it is not necessary to call finish.

Sifteo::System::paint() is backed by an internal paint controller which does a lot of work so you don't have to. Frame rate is automatically throttled. Even though each cube's graphics engine may internally be rendering at a different rate (as shown by the FPS display in Siftulator) your application sees a single frame rate, as measured by the rate at which paint calls complete. This rate will never be higher than 60 FPS or lower than 10 FPS, and usually it will match the frame rate of the slowest cube.

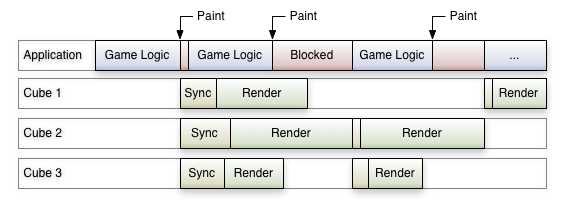

This is a simplified example timeline, showing one possible way that asynchronous rendering could occur:

Note that reality is a little messier than this, since the system tries really hard to avoid blocking any one component unless it's absolutely necessary, and some latency is involved in communicating between the system and each cube. Because of this, no guarantees are made about exactly when Sifteo::System::paint() returns, only about the average rate at which paint calls complete. If you need hard guarantees that synchronization and rendering have finished on every cube, use Sifteo::System::finish().

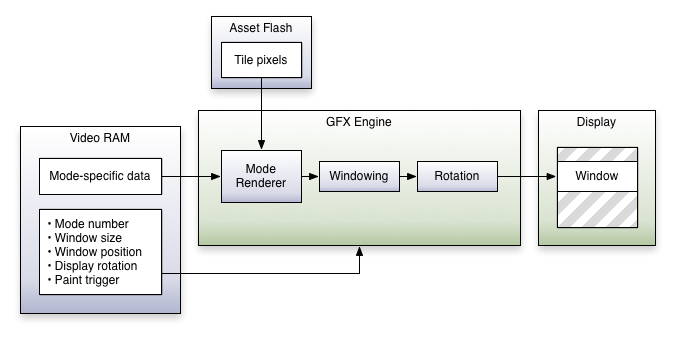

Due to the very limited amount of Video RAM available, the graphics engine defines several distinct modes, which each define a different behavior for the engine and potentially a different layout for the contents of Video RAM. These modes include different combinations of tiled layers and sprites, as well as low-resolution frame-buffer modes and a few additional special-purpose modes.

Graphics modes are all mutually exclusive. Only a single mode may be active per-cube for a given call to Sifteo::System::paint(), and that mode may interpret Video RAM in a way which wouldn't make sense in any other mode. It is common, however, for modes to define themselves as supersets of other modes. For example, the BG0 and BG0_BG1 modes are mutually exclusive, and you can only paint with one or the other. But BG0_BG1 is defined as a mode which extends the Video RAM layout and rendering model that was introduced by BG0. Other modes, like BG2, have a completely distinct Video RAM layout and rendering model. Even though you can't use both BG0 and BG2 at the same time, you could use them in rapid succession in order to render different portions of the screen.

Each of these modes fits into a consistent overall rendering framework that provides a few constants that you can rely on no matter which video mode you use:

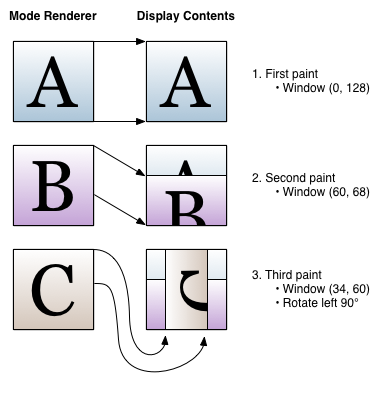

These effects can be composed over the course of multiple paint/finish operations. For example:

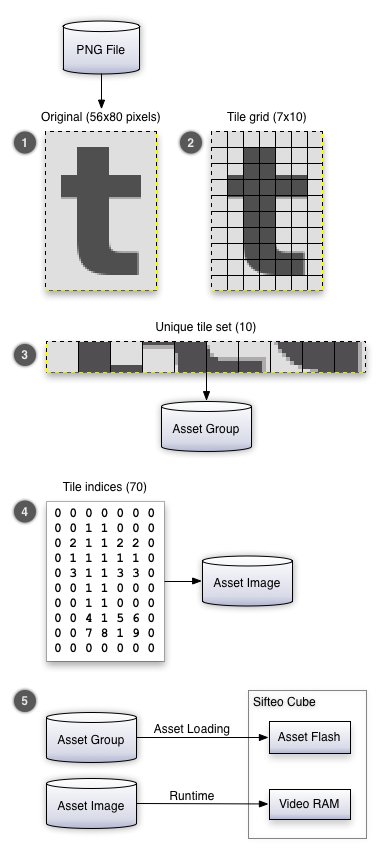

In order to make the most efficient use of the uncompressed pixel data in each cube's Asset Flash, these pixels are grouped into 8x8-pixel tiles which are de-duplicated during Asset Preparation. Any tile in Asset Flash may be uniquely identified by a 16-bit index. These indices are much smaller to store and transmit than the raw pixel data for an image.

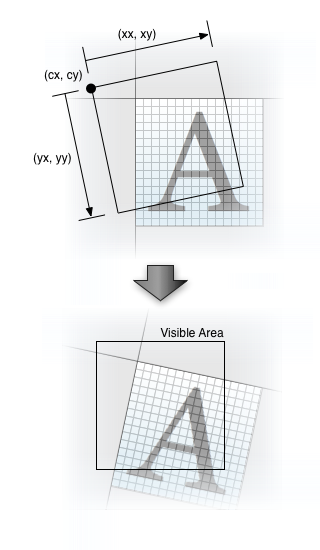

This diagram illustrates how our tiling strategy helps games run more efficiently:

For more information on how assets are stored in memory, see Asset Memory Management.

This is the prototypical tile-based mode that many other modes are based on. The name is short for background zero, and you may find both the design and terminology familiar if you've ever worked on other tile-based video game systems. Many of the most popular 2D video game systems had hardware acceleration for one or more tile-based background layers.

BG0 is both the simplest mode and the most efficient. It makes good use of the hardware's fast paths, and it is quite common for BG0 rendering rates to exceed the physical refresh rate of the LCD.

The Sifteo::BG0Drawable class understands the Video RAM layout used in BG0 mode. You can find an instance of this class as the bg0 member inside Sifteo::VideoBuffer.

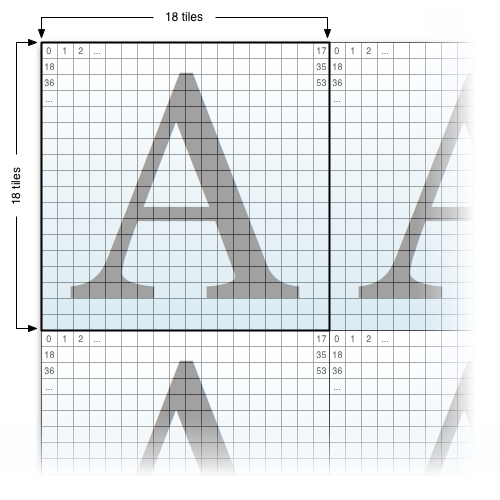

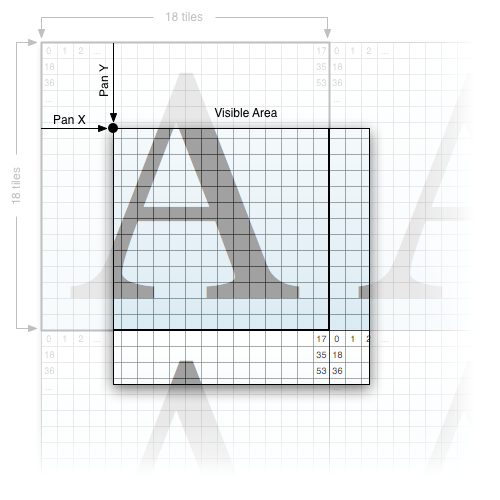

In this mode there is a single layer, an infinitely-repeating 18x18 tile grid. Video RAM contains an array of 324 tile indices, each stored as a 16-bit integer. Under application control, the individual tiles in this grid can be freely defined, and the viewport may pan around the grid with single-pixel accuracy:

If the panning coordinates are a multiple of 8 pixels, the BG0 tile grid is lined up with the edges of the display and you can see a 16x16 grid of whole tiles. If the panning coordinates are not a multiple of 8 pixels, the tiles on the borders of the display will be partially visible. Up to a 17x17 grid of (partial) tiles may be visible at any time. The 18th row/column can be used for advanced scrolling techniques that pre-load tile indices just before they pan into view. This so-called infinite scrolling technique can be used to implement menus, large side-scrolling maps, and so on.

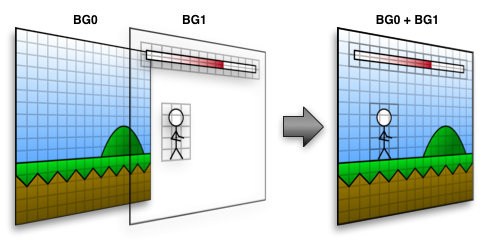

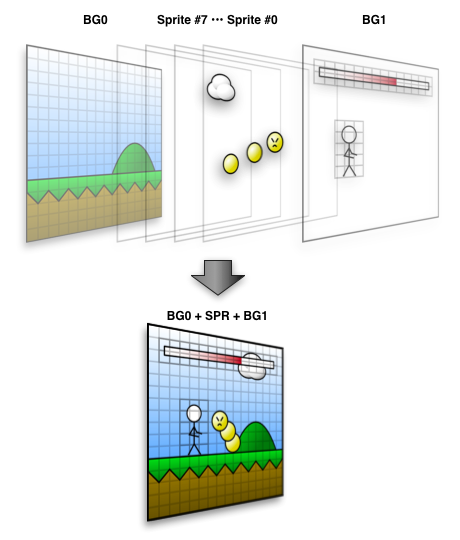

Just as you might create several composited layers in a photo manipulation or illustration tool in order to move objects independently, the Sifteo graphics engine provides a simple form of layer compositing.

Sometimes you only need a single layer. Since you can modify each tile index independently in BG0, any animation is possible as long as objects move in 8-pixel increments, or the entire BG0 layer can move as a single unit. But sometimes it's invaluable to have even a single object that "breaks the grid" and moves independently. In the BG0_BG1 mode, a second background one layer floats on top of BG0. You might use this for:

Like BG0, BG1 is defined as a grid of tile indices. You can combine any number of Asset Images when drawing BG1, as long as everything is aligned to the 8-pixel tile grid. But BG0 and BG1 use two independent grid systems; you can pan each layer independently. Additionally, BG1 implements 1-bit transparency. Pixels on BG1 which are at least 50% transparent will allow BG0 to show through. Note that Sifteo Cubes do not provide any alpha blending, so all pixels that are at least 50% opaque appear as fully opaque.

In this example, BG0 contains a side-scrolling level, and BG1 contains both a player avatar and a score meter. The avatar and score meter are stationary on the screen, so we don't need to make use of BG1's pixel-panning feature. By panning BG0, the level background can scroll left and give the appearance that the player is walking right. The tiles underlying the player sprite and the score meter can be independently replaced, in order to animate the player or change the score.

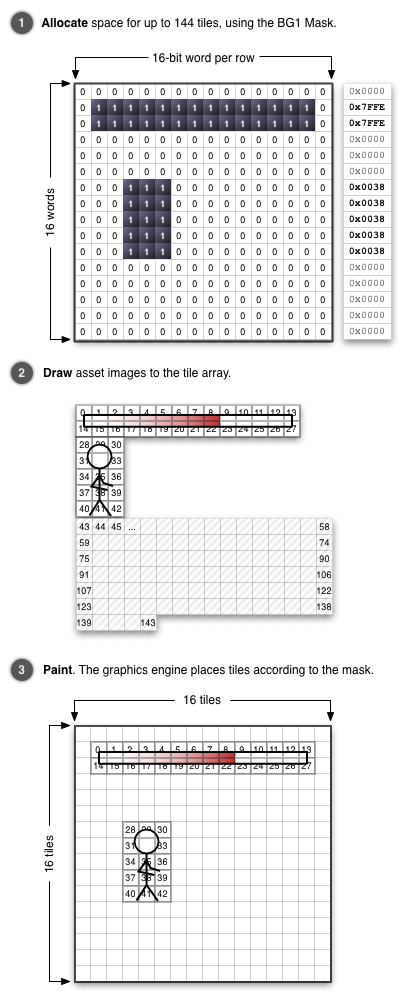

The amount of RAM available for BG1 is quite limited. Unfortunately, the Video RAM in each Sifteo Cube is too small to include two 18x18 grids as used by BG0. The space available to BG1 is only sufficient for a total of 144 tiles, or about 56% of the screen.

To overcome this limitation, BG1 is arranged as a 16x16 tile non-repeating virtual grid which can be backed by up to 144 tiles. This means that at least 112 tiles in this virtual grid must be left unallocated. Unallocated tiles always appear fully transparent.

Pixel panning, when applied to BG1, always describes the offset between the top-left corner of the virtual grid and the top-left corner of the display window. This means that the physical location of any tile depends both on the current pixel panning and on the tile's location in the virtual grid.

Tile allocation is managed by a mask bitmap. Each tile in the virtual grid has a single corresponding bit in the mask. If the bit is 0, the tile is unallocated and fully transparent. If the bit is 1, that location on the virtual grid is assigned to the next available tile index in the 144-tile array. Array locations are always assigned by scanning the mask bitmap from left-to-right and top-to-bottom.

The Sifteo::BG1Drawable class understands the Video RAM layout used for the BG1 layer in BG0_BG1 mode. You can find an instance of this class as the bg1 member inside Sifteo::VideoBuffer.

This class provides several distinct methods to set up the mask and draw images to BG1. Depending on your application, it may be easiest to set up the mask by:

There are similarly multiple ways to draw the image data, after you've allocated tiles:

Sometimes two independently-movable layers really just isn't enough. This mode adds up to eight sprites per cube, which float in-between BG0 and BG1. Each sprite can be moved fully independently. This, as you can imagine, offers a lot of flexibility. Sprites are great for particle effects, items, characters, and all manner of other doodads.

Sprites have a priority according to their index in the sprite array, from 0 to 7. Lower-numbered sprites are higher priority, and appear above higher-numbered sprites. In other words, each sprite is tested in ascending numerical order until the first opaque pixel is found.

All of this power comes with a handful of caveats, however:

The Sifteo::SpriteLayer class understands the Video RAM layout used for the sprites in BG0_SPR_BG1 mode. You can find an instance of this class as the sprites member inside Sifteo::VideoBuffer.

So far, we've been talking a lot about repositioning layers and editing tile grids, but none about common modern graphical operations like rotation, scaling, and blending. This stems from the underlying technical strengths and weaknesses of a platform as small and power-efficient as Sifteo Cubes. It's very efficient to pan a layer or manipulate tiles, but quite inefficient to do the kinds of operations you may be familiar with from toolkits like OpenGL. Modern GPUs are very good at using mathematical matrices to transform objects, but they're also very expensive and very power-hungry! The above video modes are much better at getting the most from our tiny graphics engine.

Nevertheless, sometimes you really do need to rotate or scale an image for that one special effect. Even a little bit of image transformation can make the difference between a clunky transition and a really polished interstitial animation. This is where the BG2 mode can help.

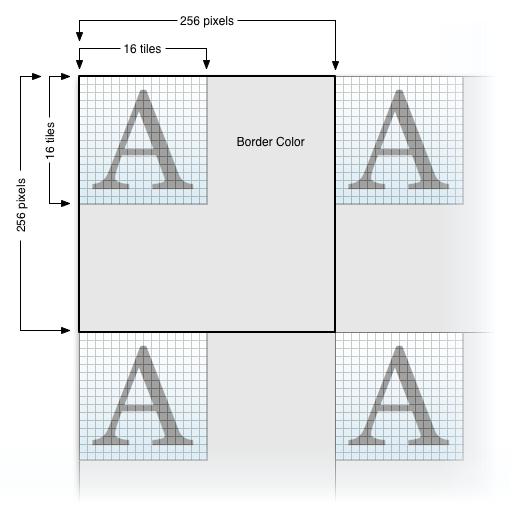

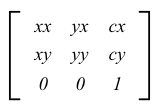

BG2 consists of a 16x16 tile grid and a matrix which applies a single affine transform to the entire scene. The layer does repeat every 256 pixels horizontally and vertically, due to 8-bit integer wraparound, but the unused portions of this 256x256 space are painted with a solid-color border. This makes it possible to scale a full-screen image down by up to 1/2 without seeing any repeats.

The entire layer is transformed via a Sifteo::AffineMatrix which is used by the graphics engine to convert screen coordinates into virtual coordinates in this repeating 256x256-pixel space:

You can think of this matrix as a set of instructions for the rendering engine:

The Sifteo::BG2Drawable class understands the Video RAM layout used in the BG2 mode. You can find an instance of this class as the bg2 member inside Sifteo::VideoBuffer.

There are a few technical limitations and caveats, of course:

All of the video modes we've discussed so far are based on assembling pixel data that has been previously stored to Asset Flash. But what if you can't count on the contents of Asset Flash? This could be the case in debugging or error handling code, or during early bootstrapping.

For these situations, the graphics engine provides the BG0_ROM mode. It is identical to the BG0 mode, except that tile data comes from an internal read-only memory region in the Sifteo Cube hardware. These tile images are installed during manufacturing, and they cannot be modified. This makes the BG0_ROM mode of limited usefulness for most applications.

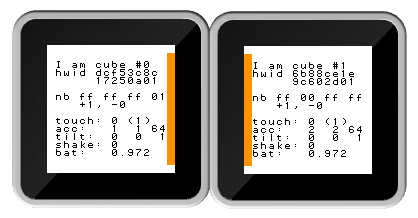

The ROM tileset does, however, include an 8x8 fixed-width font. This system font can be really handy for debugging, diagnostics, and prototyping. For example, the sensors demo uses this mode as a quick way to display text:

Tile indices in this mode are 14 bits, divided into a few distinct fields which control the rendering process on a per-tile basis:

The Sifteo::BG0ROMDrawable class understands the Video RAM layout used in the BG0_ROM mode, plus it understands the ROM tileset layout enough to draw text and progress bars. You can find an instance of this class as the bg0rom member inside Sifteo::VideoBuffer.

The simplest video mode! It draws a single solid color, from the first entry in the Sifteo::Colormap. The colormap holds up to 16 colors in RGB565 format. You can find an instance of this class as the colormap member inside Sifteo::VideoBuffer.

This mode can be used as a building block for advanced visual effects. When using windowing techniques to create a letterbox effect, for example, the SOLID mode can be used to paint a solid-color background. You can also use the SOLID mode to create bright flashes, wipes, and so on.

Unlike the tiled modes above, the SOLID mode uses Sifteo::Colormap and therefore any RGB565 color can be chosen at runtime.

The SOLID mode also has the advantage of using very little space in a cube's Video RAM. You can set up the necessary parameters for this mode very quickly, using only a small amount of radio traffic.

You might be wondering: Why do we need this Asset Flash memory at all? Can't we just send some pixels over the radio, and draw directly to a Sifteo Cube's display?

The answer: Kind of. Unfortunately, a complete framebuffer for our 128x128 16-bit display would require 32 kB of RAM, which is quite large on this system. It's much larger than the 1 kB available for each cube's Video RAM. Additionally, it would be slow to send this framebuffer image over the radio. This is a big part of why the graphics engine prefers to work with tile indices. There are so many fewer tile indices than pixels!

That said, sometimes you really do just want to draw arbitrary pixels to the screen. The graphics engine includes a small set of framebuffer modes which compromise by providing low-resolution and low-color-depth modes which do fit in the limited memory available.

The FB32 mode is a 32x32 pixel 16-color framebuffer. It requires 512 bytes of RAM, or exactly half of the Video RAM. The other half includes mode-independent data, as well as a colormap which acts as a lookup table to convert each of these 16 colors into a full RGB565 color. This 32x32 chunky-pixel image is scaled up by a factor of four by the mode renderer.

The Sifteo::FBDrawable template implements Video RAM accessors for plotting individual pixels, filling rectangles, and blitting bitmaps on to the framebuffer. Sifteo::FB32Drawable is a typedef for the specialization of this template used in FB32 mode, and you can find an instance of this class as the fb32 member inside Sifteo::VideoBuffer.

The 16-entry colormap can be independently accessed via Sifteo::Colormap, which lives in the colormap member of Sifteo::VideoBuffer. The colormap can be modified either before or after plotting pixel data. By changing the colors associated with each color index, you can perform palette animation efficiently without changing any of the underlying framebuffer memory.

The FB64 mode is another flavor of framebuffer, but this time with a different resolution vs. color depth tradeoff. It stores data for a 64x64 pixel framebuffer, which is doubled to 128x128 during rendering. However, this only leaves memory for 1 bit per pixel, or 2 colors.

This mode uses the Sifteo::FBDrawable template as well. Sifteo::FB64Drawable is a typedef for the specialization of this template used in FB64 mode, and you can find an instance of this class as the fb64 member inside Sifteo::VideoBuffer.

Only the first two entries of Sifteo::Colormap are used. The colormap lives in the colormap member of Sifteo::VideoBuffer.

The last of our pure framebuffer modes is FB128. As the name would imply, it is 128 pixels wide. Like FB64, it is 1 bit per pixel. (2-color)

This framebuffer mode does not employ any scaling. Each pixel maps directly to one pixel on the display. This makes it a much more generally useful mode, but at a cost: There is only enough RAM for 48 rows of pixels. FB128 is a 128x48 pixel mode which is repeated vertically if the display window is more than 48 rows high.

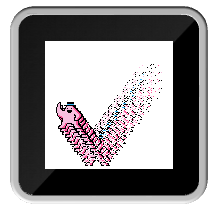

The FB128 mode is particularly useful for text rendering, since it is the most efficient way to display fonts with proportional spacing. The SDK includes a text example which makes use of the SOLID and FB128 modes:

This mode uses the Sifteo::FBDrawable template as well. Sifteo::FB128Drawable is a typedef for the specialization of this template used in FB128 mode, and you can find an instance of this class as the fb128 member inside Sifteo::VideoBuffer.

Only the first two entries of Sifteo::Colormap are used. The colormap lives in the colormap member of Sifteo::VideoBuffer.

The STAMP mode is a special-purpose framebuffer which supports tiling, two-dimensional windowing, and 1-bit color key transparency. Like its rubber namesake, this stamp is good at splatting images on top of other images.

This mode is intended for various special effects which prefer to operate in immediate mode. Instead of composing a full scene in Video RAM and drawing it all in one pass, immediate mode refers to the technique of drawing only a small part of the scene during each hardware "frame". This is analogous to other rendering models you may be familiar with, such as OpenGL, in which each primitive is independently drawn to the screen.

There are some important downsides to immediate mode rendering which typically make it inferior to the tile-based video modes above:

Nevertheless, this mode can be invaluable for certain kinds of special effects. Anything that builds up a scene gradually, such as a painting game, may use the STAMP mode as its brush. You can use this mode for full-screen stippling effects, for simulating fade-out. This mode may also be useful for text overlays.

The STAMP mode allows a portion of Video RAM to be interpreted as a framebuffer with variable dimensions. Any size may be used, as long as the width is even (making it an integral number of bytes) and the total number of pixels is less than or equal to 1536. For example, you could use a 128x12 framebuffer, or 64x24, or 32x32.

Just like the FB32 mode, we use a 16-entry color lookup table. This can be accessed via Sifteo::Colormap, which lives in the colormap member of Sifteo::VideoBuffer. One of these colormap indices may optionally be designated as the transparent "key" index. Any pixels matching that index will be skipped entirely rather than drawn to the framebuffer.

This small framebuffer repeats in both axes, just like in FB128 mode. Horizontal windowing may be used to restrict the rendering area to a box equal in size to the framebuffer. In this usage, STAMP mode can be used much like sprites, but without erasing any drawing already present on the display. If the box is smaller, the framebuffer is cropped. If it's larger, the framebuffer repeats.

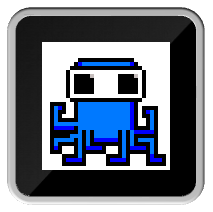

The stampy SDK example uses this video mode both to draw a sprite-like character bouncing around the screen, and to use a time-variant stipple pattern in order to "dissolve" the trail of images that is left behind as the character bounces.

The Sifteo::StampDrawable object acts as an accessor for the STAMP mode's horizontal windowing and color-keying parameters. You can find an instance of this class as the stamp member inside Sifteo::VideoBuffer. It provides accessors which retrieve a Sifteo::FBDrawable instance of the right geometry, which you may use to draw pixel data to the mode's framebuffer memory.

Sifteo SDK v1.1.0 (see all versions)

Last updated Tue Dec 23 2014, by Doxygen